|

In August 2017, the results of a Phase II double-blind, placebo controlled clinical trial investigating whether the diabetes drug Exenatide (aka Bydureon) can be repurposed for the treatment of Parkinson’s were published. Despite the fact that the study did not meet most of its end points, the Parkinson’s community got very excited about one of the results: The exenatide treated group demonstrated a stabilisation of their motor features over the 48 week trial, while the control group continued to worsen. Over night, for many in the community, the hypothetical (a “disease-halting medication”) suddenly become a possibility. After such a long trail of negative clinical trial results, it was a very human and natural response for everyone to get excited. But with the news this month, that the Phase III exenatide clinical trial is about to start, the community needs to curb that excitement in order for a proper evaluation of the drug to take place. In today’s post, we will look at the details of the new Phase III clinical trial for Exenatide and discuss why it is important to manage expections.

|

Here on the SoPD website we are often discussing novel potentially disease modifying therapies for Parkinson’s. And it is rather staggering the number and range of different approaches currently being tested on Parkinson’s.

And I am often asked, “Simon, if you were a betting man, which one I would put my money on? Which one are you expecting to work?”

Now, before we go on dear reader, please understand that my answer to this question will problably disappoint you.

You see, I do not expect any of these experimental treatments being clinically tested to work.

WHAT THE?!?

Now, before you turn off, please let me explain – because this is important (it is not click-bait).

Ok, I’m listening. Why don’t you expect any of these treatments to work?!?

A clinical trial is supposed to be an unbiased evaluation of a therapy. Thus, if you approach a trial (even as an observer) with any kind of expectations, you are biased.

So when I say that I don’t expect any of these experimental treatments being clinically tested to work, I am simply saying that I am approaching each trial with no expectations.

My comment is certainly not a negative judgement on the science (some of the biology being explored is bordering on magic to a fool like me). Nor am I questioning the researchers or the participants involved (they are the best of us).

I am simply saying that I am not expecting any particular outcome. I have:

Now, my name is not Spock and I do have high hopes for many of the therapies that we discuss here on the SoPD. BUT we need to be very careful about how we manage expectations.

And this is particularly important with regards to the Phase III exenatide study.

What is exenatide?

Exenatide (also known as bydureon and byretta) is a commonly used treatment for diabetes which the Cure Parkinson’s Trust and Van Andel Institute have been trying to repurpose for Parkinson’s. Here on the SoPD website, I have written extensively about exenatide and other “GLP-1 agonists” (Click here for an example of a SoPD post on this topic).

Exenatide was the first clinical trial of disease modification in Parkinson’s that provided ‘a signal’ – an indication of an actual effect. The results of a Phase II clinical trial were published in August 2017, and they showed that the exenatide treated group of people with Parkinson’s had a stabilisation of their motor features during the 48 week trial:

Authors: Athauda D, Maclagan K, Skene SS, Bajwa-Joseph M, Letchford D, Chowdhury K, Hibbert S, Budnik N, Zampedri L, Dickson J, Li Y, Aviles-Olmos I, Warner TT, Limousin P, Lees AJ, Greig NH, Tebbs S, Foltynie T

Journal: Lancet 2017 Aug 3. pii: S0140-6736(17)31585-4.

PMID: 28781108

In that clinical trial, 62 people with Parkinson’s (average time since diagnosis was approximately 6 years) and they randomly assigned them to one of two groups: Exenatide (the Bydureon formulation which is injected once per week) or placebo (32 and 30 people, respectively). The treatment was given for 48 weeks (in addition to their usual medication) and then the participants were followed for another 12-weeks without any treatment (exenatide or placebo) in a ‘washout period’.

It is important to understand that in this trial everyone was “blind“, meaning that both the investigators and the participants did not know which treatment each participant was receiving. This is referred to as a double-blind clinical trial and is considered the gold standard for testing the efficacy of a new drug.

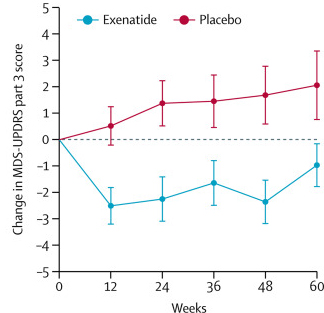

After the trial was completed, the researchers found a statistically significant difference in the motor scores of the exenatide-treated group verses the placebo group (p=0·0318). That is to say, while the placebo group continued to have an increasing (or worsening) motor score over time, the exenatide-treated group demonstrated improvements, which remarkably remained after the treatment had been stopped for 3 months (weeks 48-60 on the graph below).

Reduction in motor scores in Exenatide group. Source: Lancet

Wow! That’s amazing!

It is a good result. And a wonderful morale boost for the Parkinson’s community.

But here’s the thing: the stabilisation of motor features was the only positive result of the trial.

Exenatide showed no difference to placebo in any of the other endpoints (endpoints are the pre-determined measures that are used to test a drug). For example, there were no cognitive benefits from exenatide treatment.

Yeah, but still. The drug stopped the progression of the motor features in people with Parkinson’s, right?

Well, actually,…

Of the trial participants who were randomly assigned to the exenatide treatment group, only 45% (14/32) of the subjects had an improvement of their motor score (according to the MDS-UPDRS Part 3) of at least 3.25 points at the 48 weeks time point. These individuals were classified as “high responders”.

But some of the other participants in the exenatide treatment group had little or no response to exenatide. That is to say, the drug had no measureable effect on those individuals.

An important part of the new Phase III trial will be building up a better understanding of how we can differentiate between high responders and those who do not benefit for the sake of any future use in the clinic. The investigators behind the study have already conducted some post hoc analysis of the previous set of data, but the number of participants was too small to draw any major conclusions (Click here to read a previous SoPD post on that analysis).

While the Parkinson’s community has become very excited by the exenatide results, it it important to put them into context: The current results indicate that the drug is doing something for some people with Parkinson’s, but not all.

What do you mean by ‘something’? You don’t think it’s disease modification?

I’m not saying that.

There is currently not enough clinical evidence to make any statement regarding disease modification. This new Phase III trial will be trying to provide an answer to this question (and we will be discussing what exactly we mean by disease modification in Parkinson’s in a future SoPD post).

There is, however, already a lot of debate within the research community as to whether the effect observed in the Phase II study was disease modification or simply a symptomatic effect.

Some preclinical evidence suggests that exenatide may be boosting dopamine levels, which would provide an improvement in motor performance (possibly even when individuals are off medication). This is important as the clinical assessments in the Phase II (and new Phase III) exenatide trial were all conducted in the off state. That said, there is also preclinical evidence in animal models of Parkinson’s suggesting that GLP-1 agonists are neuroprotective, so we will have to wait and see what the results of the Phase III clinical trial of exenatide report.

I see. So what do we know what this new Phase III study?

The study – which is being funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and supported by the Cure Parkinson’s Trust and Van Andel Institute (via the co-funding of substudies) – will be conducted across 6 UK research sites:

2. University Hospitals Plymouth NHS Trust

3. NHS Lothian

4. Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

5. King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

6. Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust

It will be a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, Phase III trial of once weekly exenatide (Bydureon) as a potential disease-modifying treatment for Parkinson’s. The study will recruit 200 people with Parkinson’s and they will be randomly assigned to either the treatment or placebo group.

Both groups will then be treated and assessed for 2 years (Click here to read the details about the study). One of the goals of the study will be to see whether the potentially neuroprotective effect reported in the phase II study “can be reproduced in a multi-centre setting including a larger number of participants. An important objective is to explore whether any positive effects remain static or increase when the treatment is continued over a 96 week period“.

Why the long time frame?

The long time frame is to provide a better assessment of whether any effect observed in the study is symptomatic or actually disease modification. Two years on drug or placebo is a major commitment for the individuals volunteering to participate in the study though.

So what does it all mean?

This was a difficult post to write, but it felt necessary for these things to be said.

The writing was difficult because expectations can go in different directions quite easily. If we raise expectations by discussing all the positives of a drug, then there is great chance of a placebo response. Alternatively, if we pour negativity on the whole story, we can increase the chance of a nocebo response

I have been contacted by a number of individuals who are very excited about the new Phase III exenatide trial and their high expections have concerned me. Honestly, clinical trials for Parkinson’s would be so much easier if we could just take the humans out of them. But seriously, if we as a community go into a clinical trial with high expectations, it is not going to be an unbiased evaluation of the experimental therapy.

There is a lot of ‘hope’ riding on the Phase III exenatide trial, but we have to now manage our expectations and simply get on with the job of evaluating the drug. We need to assess the treatment in an unbaised fashion and learn as much as we can. And I appreciate that all of this is very easy to say when one is not actually affected by the condition, but I also understand that tremendous resources are being deployed for this study and there will be additional future Phase III trials for other drugs coming soon, and it felt appropriate to discuss the matter of expectations here and now.

And as stated above I have no expectations regarding any of those clinical trials, and I hope others will join in this philosophy.

The banner for today’s post was sourced from dsds2009