|

# # # # A class of diabetes drugs called GLP-1 receptor agonists have exhibited neuroprotective properties in models of Parkinson’s, and a Phase IIb clinical trial produced encouraging. This research has led to a number of parties to start investigating new and old GLP-1 receptor agonists for their potential to slow the progression of Parkinson’s. Recently, the results of a second Phase II clinical trial investigating a GLP-1 agonist were announced. The agonist being tested was liraglutide. In today’s post, we will discuss what GLP-1 receptor agonists are, what research has been conducted in PD, and look at the recent clinical trial announcement. # # # # |

The name “Golden Goose Award” doesn’t really conjure images of an inspirational kind of accomplishment. It does not suggest the same kind of gravitas that the Nobel prize carries.

In fact, it sounds rather comical: The golden goose award? Sounds like a children’s book writers award.

And yet…

The Award was originally established in 2012 with the goal of celebrating researchers whose seemingly odd or obscure federally funded research turned out to have a significant and positive impact on society as a whole.

And despite the name, it is a very serious award – past Nobel prize winners (such as Roger Tsien, David H. Hubel, and Torsten N. Wiesel) are among the awardees.

In 2013, it was awarded to Dr John Eng, an endocrinologist from the Bronx VA Hospital.

Dr John Eng. Source: Health.USnews

What did Dr Eng do to deserve the award?

In the 1980’s, Dr Eng became really interested in some studies (such as this one) that described the effects that certain types of venom had on cells in the pancreas.

Remind me, what is the pancreas?

The pancreas is the organ that produces the chemical insulin, which is critical for maintaining normal glucose levels in our bodies. The pancreas is located below the stomach.

Previous research suggested that venom could stimulate the pancreas to release insulin. Having worked with diabetic people who do not produce enough insulin, Dr Eng started wondering if venom may useful for people with diabetes. But rather than simply injecting diabetic people with venom (hands up who wants to be part of that clinical study?), he started looking at all the chemicals that make up the venom from different poisonous creatures.

What did he find?

This charming creature is a Gila monster.

The Gila monster. Source: Californiaherps

Cute huh?

Some interesting facts about the Gila (pronounced ‘Hila’) monster:

- They are named after the Gila River Basin of New Mexico and Arizona (where these lizards were first found)

- They are protected by State law

- They are venomous, but very sluggish creatures

- They spend 95 percent of their time underground in burrows.

In 1992, Dr Eng identified the two proteins that he had isolated from the venom of the Gila monster. One of them was called exendin-4 and it bore a striking similarity – structurally and functionally – to a human protein, called glucagon like peptide-1 (or GLP-1).

What is GLP-1?

Insulin instructs cells to take in and use glucose from the blood. This has the effect of lowering blood sugar. The hormone Glucagon has the opposite effect – it tells the body to release glucose into the blood to raise sugar levels.

GLP-1 is a gut-produced hormone that stimulates insulin production while blocking glucagon release.

The function of GLP-1. Source: Wikipedia

Unfortunately, naturally produced GLP-1 in your body is rapidly deactivated by a circulating enzyme called dipeptidyl peptidase IV (or DPP-4 – click here to read a previous SoPD post on this enzyme). Exendin-4, however, was found to be resistant to this deactivation, meaning that could last longer in the body stimulating insulin production and blocking glucagon release.

Dr Eng quickly realised that there was enormous medicinal potential for exendin-4 as a drug for people with diabetes. He patented the idea and soon afterwards a biotech company called Amylin Pharmaceuticals to begin the work of turning exendin-4 into a drug for diabetes.

That drug was eventually called Exenatide.

In April 2005, Byetta (the commercial name for Exenatide) was approved by the FDA for clinical use in the treatment of Type 2 diabetes. On the 27th January 2012, the FDA gave approval for a new formulation of Exenatide called Bydureon, as the first weekly treatment for Type 2 diabetes. In July of 2012, Bristol-Myers Squibb announced it would acquire Amylin Pharmaceuticals for $5.3 billion, and one year later AstraZeneca purchased the Bristol-Myers Squibb share of the diabetes joint venture.

|

# RECAP #1: GLP-1 is a gut-produced hormone that stimulates insulin production. A drug called exenatide is very similar to GLP-1 and it is used to treat people with diabetes. Many biotech companies have developed similar agents to exenatide. # |

Interesting, but what does any of this have to do with Parkinson’s?

In 2008, this report was published:

Title: Peptide hormone exendin-4 stimulates subventricular zone neurogenesis in the adult rodent brain and induces recovery in an animal model of Parkinson’s disease.

Authors: Bertilsson G, Patrone C, Zachrisson O, Andersson A, Dannaeus K, Heidrich J, Kortesmaa J, Mercer A, Nielsen E, Rönnholm H, Wikström L.

Journal: J Neurosci Res. 2008 Feb 1;86(2):326-38.

PMID: 17803225

In this study, Exendin-4 (the protein very similar to exenatide) was tested in a rat model of Parkinson’s. Five weeks after giving the neurotoxin (6-hydroxydopamine) to the rats, the investigators began treating the animals with exendin-4 over a 3 week period. Despite the delay in starting the treatment, the researchers found behavioural improvements and a reduction in the number of dying dopamine neurons.

And this first result was followed a couple of months later by a similar report with a very similar set of results:

Title: Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor stimulation reverses key deficits in distinct rodent models of Parkinson’s disease.

Authors: Harkavyi A, Abuirmeileh A, Lever R, Kingsbury AE, Biggs CS, Whitton PS.

Journal: J Neuroinflammation. 2008 May 21;5:19. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-19.

PMID: 18492290 (This study is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

The scientists in this study tested exendin-4 on two different rodent models of Parkinson’s (6-hydroxydopamine and lipopolysaccaride), and they found similar results to the previous study. The drug was given 1 week after the animals developed the motor features, but the investigators still reported positive effects on both motor performance and the survival of dopamine neurons.

And the following year, in 2009, two more research reports were published suggesting that exendin-4 was having positive effects in models of Parkinson’s (Click here and here to read those reports).

This was a lot of positive results for this little molecule.

How is Exendin-4/Exenatide having this positive effect?

Exendin-4 and exenatide are both GLP-1 receptor agonists.

What does that mean?

On the surface of cells there are small proteins called receptors, which act like switches for certain biological processes. Receptors will wait for another protein to come along and activate them or alternatively block them.

The proteins that activate the receptors are called agonists, while the blockers are called antagonists.

Agonist vs antagonist. Source: Psychonautwiki

Exendin-4 and exenatide are agonists, so they activate the GLP-1 receptor – they act the same as GLP-1 which binds to and activates the GLP-1 receptor.

Activation of the GLP-1 receptor by a GLP-1 receptor agonist like exendin-4 or exenatide results in the activation of many different biological pathways within a cell:

The GLP-1 signalling pathway. Source: Sciencedirect

Of particular importance is that GLP-1 receptor activation inhibits cell death pathways, reduces inflammation, reduces oxidative stress, and increases neurotransmitter release. All pretty positive stuff really (Click here for a very good OPEN ACCESS review of the GLP-1-related Parkinson’s research field).

And all of these preclinical research reports with positive results led to and supported the idea of clinically testing exenatide in people with Parkinson’s.

What happened in the first clinical trial?

The first clinical trial of exenatide in Parkinson’s was a Phase IIa trial to determine if the drug was safe to use in people with Parkinson’s. The results of the trial were published in 2013:

Title: Exenatide and the treatment of patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Authors: Aviles-Olmos I, Dickson J, Kefalopoulou Z, Djamshidian A, Ell P, Soderlund T, Whitton P, Wyse R, Isaacs T, Lees A, Limousin P, Foltynie T.

Journal: J Clin Invest. 2013 Jun;123(6):2730-6.

PMID: 23728174 (This study is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

The researchers gave exenatide (the Byetta formulation which is injected twice per day) to a group of 21 people with moderate Parkinson’s and evaluated their progress over a 14 month period. They compared those participants to 24 additional subjects with Parkinson’s who acted as control (they received no treatment). Exenatide was well tolerated by the participants, although there was some weight loss reported among many of the subjects (one subject could not complete the study due to weight loss).

Importantly, the exenatide-treated subjects demonstrated improvements in their Parkinson’s movement symptoms (as measured by the Movement Disorders Society Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (or MDS-UPDRS)), while the control patients continued to decline.

Interestingly, in a two year follow up study – which was conducted 12 months after the subjects stopped receiving exenatide – the researchers found that participants previously exposed to exenatide demonstrated a significant improvement (based on a blind assessment) in their motor features when compared to the control subjects involved in the study.

It is important to remember, however, that this trial was an ‘open-label study’ – that is to say, the participants knew that they were receiving the exenatide treatment so there is the possibility of a placebo effect explaining the improvements. And this necessitated the testing of the efficacy of exenatide in a Phase IIb double blind clinical trial.

And the results of that trial were published last August (2017):

Authors: Athauda D, Maclagan K, Skene SS, Bajwa-Joseph M, Letchford D, Chowdhury K, Hibbert S, Budnik N, Zampedri L, Dickson J, Li Y, Aviles-Olmos I, Warner TT, Limousin P, Lees AJ, Greig NH, Tebbs S, Foltynie T

Journal: Lancet 2017 Aug 3. pii: S0140-6736(17)31585-4.

PMID: 28781108 (This report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In the study, the investigators recruited 62 people with Parkinson’s (average time since diagnosis was approximately 6 years) and they randomly assigned them to one of two groups, exenatide (the Bydureon formulation which is injected once per week) or placebo (32 and 30 people, respectively). The treatment was given for 48 weeks (in addition to their usual medication) and then the participants were followed for another 12-weeks without exenatide (or placebo) in a ‘washout period’.

It is important to remember that in this trial everyone was blind. Both the investigators and the participants. This is referred to as a double-blind clinical trial and is considered the gold standard for testing the efficacy of a new drug.

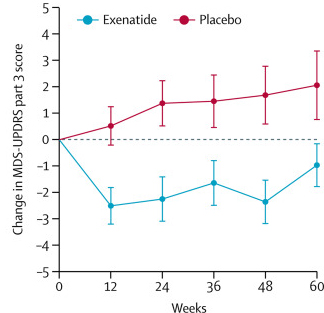

The researchers found a statistically significant difference in the motor scores of the exenatide-treated group verses the placebo group (p=0·0318). As the placebo group continued to have an increasing (worsening) motor score over time, the exenatide-treated group demonstrated improvements, which remarkably remained after the treatment had been stopped for 3 months (weeks 48-60 on the graph below).

Reduction in motor scores in Exenatide group. Source: Lancet

Brain imaging (DaTScan) also suggested a trend towards a reduced rate of decline in the exenatide-treated group when compared with the placebo group. Interestingly, the researchers found no significant differences between the exenatide and placebo groups in scores of cognitive ability or depression – suggesting that the positive effect of exenatide may be more specific to the dopamine or motor regions of the brain.

Given that these results were coming from a randomised, double-blind clinical trial, the Parkinson’s community got rather excited about them (Click here to read a previous SoPD post about this particular trial).

A Phase III clinical trial of exenatide (again, the Bydureon formulation) is now underway at 6 sites in the UK (Click here to read more about this). We look forward to seeing the results of that study in late 2024.

Interesting. Are there other clinical trials of GLP-1 receptor agonists in Parkinson’s?

Yes, the results of the Phase IIb study have generated a lot of interest – from both academia and industry. By my count there are at least seven ongoing (and one recently completed) clinical trials of GLP-1 receptor agonists for Parkinson’s. They are the:

- Phase III study of Exenatide in Parkinson’s study in the UK

- Phase II study of Lixisenatide in Parkinson’s study in France (reporting results in late 2022)

- Phase II study of Semaglutide in Parkinson’s study in Norway

- Phase II study of NLY01 in Parkinson’s study across the USA (being conducted by Neuraly – reporting results in 2023)

- Phase II study of PT320 in Parkinson’s in South Korea (being conducted by Peptron -reporting results in 2022)

- Phase II study of Exenatide trial in Parkinson’s in Sweden

- Phase I study of Exenatide in Parkinson’s study in Florida

The recently completed trial is a Phase II study investigating the effects of liraglutide in people with Parkinson’s.

|

# # RECAP #2: GLP-1 receptor agonists are a class of drugs that stimulate the GLP-1 receptor, causing the release of insulin. Exenatide was the first GLP-1 receptor agonist that was developed. Exenatide has demonstrated interesting neuroprotective properties in models of Parkinson’s, and early clinical trial results suggest these effects may translate to humans. More studies are ongoing to validate these effects and determine the utility of this class of drugs in Parkinson’s. # # |

Are the results of the recently completed clinical trial available?

Before we go any further – I need to make a full disclosure – the author of this blog is an employee of this charitable research trust, Cure Parkinson’s . In addition to supporting much of the other GLP-1 receptor agonist research discussed above, Cure Parkinson’s was a funder of the Phase II study investigating liraglutide in Parkinson’s.

The results of the liraglutide study have not been published, but they were announced and presented at the recent American Academy of Neurology 2022 conference in Seattle.

The study was the conducted at Cedar Sinai in Los Angeles. It involved 63 participants being recruited and randomly assigned (at a ratio of 2:1) to receive either liraglutide (6 mg/ml once daily; Novo Nordisk A/S) or a placebo treatment. The participants were then regularly assessed by the research team for 52 week. The primary endpoint of the study (the pre-determined measure of success for the study) was the changes in the MDS-UPDRS (part III) motor score and the change in non-motor symptoms (as assessed by the NMSS and MDRS-2) after 52 weeks of treatment (Click here to read more about this study).

So the effectiveness of liraglutide was determined based on how much effect it had on the progression of motor and non-motor symptoms, as determined by clinical assessments.

The study team was led by Prof Michele Tagliati of the Cedar Sinai medical centre.

The presented results (Source) indicated that of the study participants, 37 people were on liraglutide and 18 on the placebo treatment. The 52 weeks of daily liraglutide treatment was found to be safe and well tolerated.

Unfortunately, there was no significant difference between the liraglutide treated group and the placebo group when the investigators looked at motor symptom scores after 1 year of treatment. Both groups appear to have improved slightly. It could be that there was a placebo response at play there (a placebo response being an effect where there is no biological explanation).

But interestingly, the researchers did see a statistically significant response in the non-motor symptoms: The liraglutide treated group experienced improvements in measures of non-motor symptoms, activities of daily living and quality of life, while the placebo group did not.

Curiously, the liraglutide treated group also reported significant mobility improvements in their self assessments questionnaires. Theses are different to the clinician rated motor scores of the primary endpoint.

For those interested in learning more about the results, you can watch this video of Prof Tagliati presenting the initial findings:

So what happens next?

This is yet to be decided. There is a follow-up period involved with this study of up to 14 months which is still occurring. Plus the extended results are still being analysed, so there is still work to be done.

Based on the initial results, however, it would be interesting to compare these findings with the results of the other GLP-1 receptor agonist clinical trials and see what commonalities exist. It is intriguing that the Phase IIb exenatide study saw a motor benefit, but limited non-motor improvements, and now this study has a significant non-motor result, but mixed motor results.

Hopefully before the end of the year we will have additional data from the lixisenatide and PT320 Phase II studies which will add to our knowledge of this drug class in Parkinson’s.

So what does it all mean?

At the top of this post I wrote that the golden goose award sounds like a children’s book writers award. The name ‘Golden goose’ actually did originate from a children’s book. First published on 20 December 1812, “The Golden Goose” (Die goldene Gans) was one of 86 stories in the first edition of Grimm’s Fairy Tales. The hero in the story is the youngest of three brothers, given the nickname “Simpleton” who is rewarded for an act of generosity with a golden goose. In the end of the tale, Simpleton is unexpectedly wins the hand of a local princess and they all live happily ever after. Fingers crossed we are heading for a similar fate with GLP-1 receptor agonists.

These new liraglutide results are encouraging and provide further support that this class of drugs is doing something interesting in the context of Parkinson’s. The ongoing Phase III study will provide the largest and longest assessment, but until that trial reports in 2024, there will be a continuing stream of related results from smaller Phase II studies. In addition, we may see the initiation of trials examining the next generation of GLP-1 receptor related therapeutics in Parkinson’s: dual agonists.

A biotech company called Kariya Pharmaceticals is developing a drug called KP405, which combines a GLP-1 receptor agonist with a glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (or GIP) agonist. Dual-agonist combinations are being developed for diabetes (see Tirzepatide from Eli Lilly or BI 456906 from Zealand Pharma), but KP405 has been designed to penetrate the blood brain barrier for testing in neurodegenerative conditions. Like GLP-1, GIP also stimulates insulin secretion (Click here to read more about this). And like GLP-1, agonists of GIP have been reported to be neuroprotective in models of Parkinson’s (Click here and here to read more about this).

So there is a lot of exciting developments to keep an eye on in this area of Parkinson’s research.

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

You can do whatever you like with it!

EDITOR’S NOTE: The information provided by the SoPD website is for information and educational purposes only. Under no circumstances should it ever be considered medical or actionable advice. It is provided by research scientists, not medical practitioners. Any actions taken – based on what has been read on the website – are the sole responsibility of the reader. Any actions being contemplated by readers should firstly be discussed with a qualified healthcare professional who is aware of your medical history. While some of the information discussed in this post may cause concern, please speak with your medical physician before attempting any change in an existing treatment regime.

The author of this post is an employee of Cure Parkinson’s, so he might be a little bit biased in his views on trials supported by the trust. That said, the trust has not requested the production of this post, and the author is sharing it simply because it may be of interest to the Parkinson’s community.

The banner for today’s post was sourced from clinicaltrialsarena.