|

# # # # Assessing the progression of Parkinson’s is a very difficult task, but accurately doing so is critical to our ability to evaluate the disease modifying potential of new therapies. The clinical measures currently used in clinical trials have been developed using large longitudinal studies that assessed individuals over long periods of time. But the utility of these tools have been called into question as we try to measure subtle changes in progression. Using post-hoc (after the fact) analysis of recent clinical trial data, however, researchers have recently proposed a new method of assessment that they call “The Parkinson’s Disease Comprehensive Response” (or PDCORE). In today’s post, we will discuss what PDCORE is and how it was identified. # # # # |

I am not a climber (in fact, despite being rather tall, I am not very good at heights).

I certainly do not understand the mentality of people that need to climb mountains just to reach the top, particularly if they are simply following the same route as every other person climbing the same peak. And images of traffic jams in the “death zone” (above 8,000 meters) of Everest completely befuddle me.

So on the 15th April of this year when I heard about the passing of a climber named Joe Brown, I thought nothing of it… until that is, I read his story.

And more importantly his philosophy.

You see, Joe was deeply passionate about climbing and was considered one of the best by many. But for Joe it was never about getting to the top of the mountain, it was always about finding a new route up a mountain or a new way of doing something that compelled him.

This is a mentality I can appreciate.

It is also an idea that the Parkinson’s research community needs to embrace. If we are simply doing things because they are the way we have always done things, something is wrong.

Like Joe Brown, we need to be exploring new routes.

Which is why in today’s post we will be discussing PDCORE.

What is PDCORE?

Before we answer that, a little bit of background:

Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (or GDNF) is a neurotrophic factor. This is a protein that supports the development and survival of neurons. GDNF is particularly good at rescuing dopamine neurons – the population of cells affected by PD – in models of Parkinson’s.

On the 27th February (2019) the long-awaited results of a Phase II Bristol clinical trial of GDNF in Parkinson’s were published.

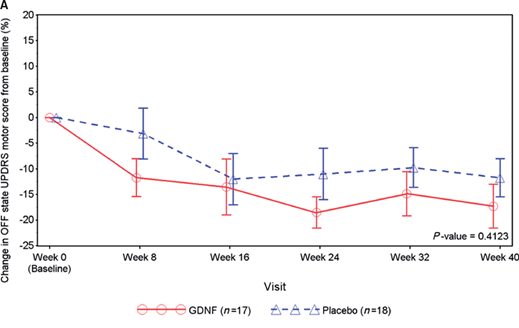

The results suggested that the treatment appeared to be having an effect in the brain (based on imaging data), but the clinic-based method of assessment (OFF UPDRS) that were used as the determinant of efficacy indicated that there was no significant effect between the treatment and placebo groups.

In fact, as you can see in the figure below, both of the groups improved across the course of the 40 week study (a downward trajectory indicates improvement in symptoms – Click here to read a previous SoPD post on this results).

The fact that the control had improvements suggests a ‘placebo response’ in some of the participants. This is a beneficial effect based on no obvious pharmacological effect. It is a common issue in Parkinson’s related clinical trials and is believed to involve the chemical dopamine.

When the researchers looked deeper into the data, however, they started to notice some interesting features.

First, when they looked at the number of participants who achieved a better than 10 point improvement on the clinical rating score, there were 9 who experienced this in the GDNF group, but none in the placebo treated group. While there were many individuals who appear to have had a “placebo response” in the control/placebo-treated group, none of them had a response as big as the GDNF responders.

And you can see this is the graphs below. On the left (GDNF treated group), there are 9 red bars beyond the >10 point responder line, but on the right (blue) side there are none.

In addition, there was the brain imaging data.

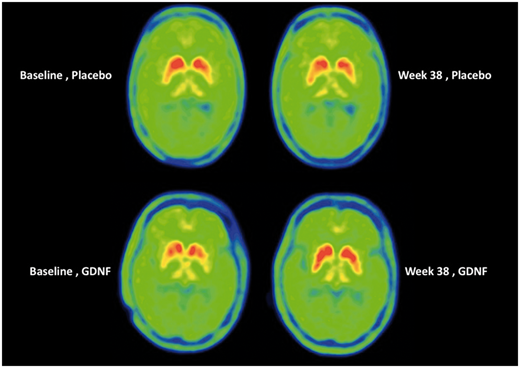

Have a look at the image below:

Each of the 4 green circles represents a birds-eye view of the brain. The red/yellow regions are the putamen on each side of the brain, and the greater the intensity of red colouration, the greater the level of dopamine activity. Now, if you look at the two brains in the top row, these are images from the same individual (baseline image on the left and 40 week image on the right). Note the subtle reduction in red colouration in the right (40 weeks) image compared to the left (baseline) image (particularly around the bottom tips of the putamen). This loss of red colouration suggests a reduction in dopamine activity. The images in the top row came from an individual who was treated with the placebo during the study.

Now shift your attention to the bottom row of brain images, and note the increase in red colouration in the right hand image (the 40 week timepoint). I hope you will agree that compared to the baseline image (left), there is a lot more red colouration on the 40 weeks (right) image. This difference suggests an increase in dopamine activity.

Interpretation of this imaging data could be debated till the cows come home, but my point is: there were pieces of data that made the researchers ask if a better measure of efficiacy might be required.

In addition, there were participants involved in the trial who felt that the overall result did not reflect what they were experiencing, and they were frustrated by the insensitivity of the clinical rating scale that was used to assess their symptoms over time.

They too were thinking that a better measure of efficiacy might be required.

|

# RECAP #1: Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (or GDNF) is a protein that supports the development and survival of neurons. The results of a Phase II clinical trial of GDNF in people with Parkinson’s found no difference between a GDNF treated group and a placebo treated group. Researchers and participants involved in the study shared concerns about the senstivity of the clinical rating scale that was used to determine efficacy in the study. # |

What was the “clinical rating scale used to determine efficacy” in the GDNF trial?

The primary endpoint (which is the predetermined measure of whether the trial was successful or not) of the Bristol trial was the percentage of change from the baseline measure in the OFF state UPDRS motor score (part III) after 40 weeks of double-blind treatment.

What does any of that mean?

It means that the investigators were assessing how much degree of improvement was observed in participants (when they are not on their medication) at the end of the trial (4 weeks) compared to the start (or baseline measures).

“OFF state” means no medication overnight or during the morning of the clinical assessment.

What is the UPDRS?

The “Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale” (or UPDRS) is a standardised clinical method that is widely used for assessing Parkinson’s.

It is considered “the gold standard“, and many (if not most) clinical trials focused on disease modification use it for measuring their primary end point (determining whether a treatment has worked or not).

What does the UPDRS involve?

The current version of the UPDRS has four parts:

- I: Non-motor experiences of daily living

- II: Motor experiences of daily living/Activities of daily living

- III: Motor examination (this part was the focus of the GDNF clinical trial primary endpoint)

- IV: Motor complications.

The MDS-UPDRS rates 65 items in comparison to 55 on the original UPDRS. 48 of these items have a 0 to 4 option (0 = normal, 5 = severe) and 7 yes/no response items. And the items are divided across the 4 parts of the UPDRS:

- Part I – 13 items

- Part II – 13 items

- Part III – 33 items (in effect there is only 18 items, but several address which side of the body, or which limb is affected)

- Part IV – 6 items

Twenty items are completed by the patient/caregiver.

It is estimated that the UPDRS should only take 30 minutes in the clinic, with 10 min for the interview items of Part I, 15 min for the motor assessment of Part III, and 5 min for motor complications of Part IV (Several items in Part I and all of the questions on Part II are filled in by the patient at their leisure).

And this is not the first version of the rating scale.

It was originally developed in the 1980s, and consisted of 42 items (Click here to see an example of the original). It was widely adopted and used, but limitations with the scale were noted and in the early 2000s, this report was generated:

Authors: Movement Disorder Society UPDRS Revision Task Force.

Journal: Mov Disord. 2003 Jul;18(7):738-50.

PMID: 12815652

In this report, the Movement Disorder Society UPDRS Revision Task Force recommended that the Movement Disorder Society should sponsor the development of a new version of the UPDRS based on several issues that had been communicated following usage of the old UPDRS. These issues included:

- ambiguities in the text

- the need for better instructions for raters

- several metric flaws

- the need for screening questions on non-motor aspects of Parkinson’s

The last issue in particular was important in the revision.

The task force also encouraged efforts to establish its “clinimetric properties”, which would address the need to accurately define what the minimal clinically relevant difference is and a Minimal Clinically Relevant Incremental Difference, as well as testing its correlation with the current UPDRS.

Critically, the task force also suggested that the new scale should be culturally unbiased and evaluated in different racial, gender, and age-groups.

The result of this process was the publication of a revised UPDRS:

Authors: Goetz CG, Tilley BC, Shaftman SR, Stebbins GT, Fahn S, Martinez-Martin P, Poewe W, Sampaio C, Stern MB, Dodel R, Dubois B, Holloway R, Jankovic J, Kulisevsky J, Lang AE, Lees A, Leurgans S, LeWitt PA, Nyenhuis D, Olanow CW, Rascol O, Schrag A, Teresi JA, van Hilten JJ, LaPelle N; Movement Disorder Society UPDRS Revision Task Force.

Journal: Mov Disord. 2008 Nov 15;23(15):2129-70.

PMID: 19025984

In 2008, the Movement Disorder Society published a revision of the UPDRS, which was now known as the MDS-UPDRS.

The modified UPDRS retained the original four-scale structure, but there was significant reorganisation of the various subscales, which we outlined above. And it is this version of the UPDRS that is now used widely in clinical trials, particularly the UPDRS Part III (which is focused on motor symptoms as determined by the assessing clinician). Primary and secondary end points in Parkinson’s clinical trials will often involve participants being assessed on the UPDRS Part III during OFF state (no medication since the night before) and the ON state (standard medication).

You can see that the UPDRS is well characterised and has been adapted over time.

But still, it is not without its criticisms, particularly within the context of clinical trials assessing disease modification.

For example, the UPDRS total score is tallied using a collection of nominal values (a nominal value is one that is assigned rather than calculated). This situation can skew data based on the section with the highest nominal value (typically in the cases of the UPDRS, this is the motor section).

|

# # RECAP #2: The “Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale” (or UPDRS) is a standardised clinical rating scale that is widely used for assessing Parkinson’s. It provides a score based on a wide range of motor and non-motor assessments, but many of the scores are nominal, meaning that they are assigned rather than calculated. # # |

So when are you going to tell me what PDCORE is?

In the wake of the Phase 2 Bristol clinical trial of GDNF in Parkinson’s, some of the researchers involved in the study decided to conduct a post hoc analysis of all of the clinical data that they had collected over the study.

And there was a lot of it!

Wait a minute. What is post hoc analysis?

A post-hoc analysis involves researchers looking at the data after an experiment/study has been concluded, and trying to identify patterns/trends that were not part of the primary objectives of the study.

Importantly, the main goal/use of post hoc analysis is ‘hypothesis generation’ – that is, it is a means of looking for new questions to ask based on a deep drive into the old data. The words ‘Post hoc’ come from the Latin meaning ‘after this’.

To do their analysis properly, the researchers asked Prof Glenn Stebbins to be part of the project.

Dr Stebbins is a professor of neurological sciences at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, but he is world renowned for his work in clinimetric and psychometric theory. He is also program chair of the MDS Rating Scales Program Committees (which oversee the development of rating scales like the MDS-UPDRS).

He certainly knows what he is talking about when it comes to the assessment of Parkinson’s (you might notice his name in the list of authors on one of the UDPRS reports above).

Ok, so PDCORE?

Indeed.

The researchers worked with what they had (the GDNF trial data) and they attempted to identify established Parkinson’s clinical outcomes that if pooled together as a “composite score” might more accurately and more senstively reflect changes in people with Parkinson’s.

A composite score involve combining items that represent a variable to create a score.

After completing their analysis of the GDNF trial data, the researchers wrote up their approach and the results and recently published it in this report:

Authors: Luz M, Whone A, Bassani N, Wyse RK, Stebbins GT, Mohr E

Journal: Brain Communications, fcaa046 early e-published 08 May 2020

PMID: N/A (This report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

During their review of the Bristol GDNF clinical trial results, the researchers noticed that individual subjects were not always the same with respect to the change observed in 3 key measures of unmasked disease:

- Change from baseline in the OFF state UPDRS motor;

- Activities of daily living scores; and

- Change from baseline in total good-quality ON time

These tests scored consistently better in the GDNF treated group at all of the post-baseline assessments. The researchers put these three measures into a composite, and called it the “Parkinson’s Disease Comprehensive Response” (or PD-CORE) score.

Next, the researchers conducted a range of exploratory analyses to better understand the impact of employing different weightings to these individual components and determine a final version of the PDCORE. A total of 432 analyses were performed, and they were all statistically in favor of GDNF.

Eventually they came to a simple formula:

PDCORE = (1 × change in OFF state motor score) + (2 × change in OFF state ADL score) – (10 × change in total good-quality ON time per day)

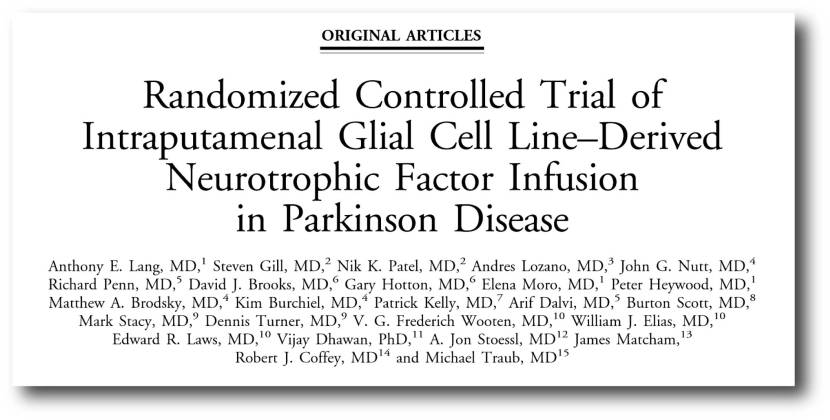

They also conducted some secondary analyses which included assessing the performance of their PDCORE composite score on a separate earlier randomized, placebo-controlled study of GDNF in patients with Parkinson’s: The Amgen Phase 2 Study.

This was the study here:

Authors: Lang AE, Gill S, Patel NK, Lozano A, Nutt JG, Penn R, Brooks DJ, Hotton G, Moro E, Heywood P, Brodsky MA, Burchiel K, Kelly P, Dalvi A, Scott B, Stacy M, Turner D, Wooten VG, Elias WJ, Laws ER, Dhawan V, Stoessl AJ, Matcham J, Coffey RJ, Traub M.

Journal: Ann Neurol. 2006 Mar;59(3):459-66.

PMID: 16429411

When the investigators used the PDCORE composite score to assess the data from this previous GDNF clinical trial it did not change the outcome – there was still no difference between GDNF and placebo treated groups in that study. The researchers proposed that this was not surprising as insufficient drug distribution in the putamen may have been the reason for a lack of effect in that study (Source).

It will be interesting to see this composite evaluated on other completed clinical trials.

And the researchers agree. In their concluding remarks, they stress that their post hoc analyses do not provide any proof of efficacy for GDNF. But they do suggest that using PDCORE in future disease-modifying Parkinson’s trials might provide a more sensitive method of assessment.

This will need to be tested.

|

# # # RECAP #3: “Parkinson’s Disease Comprehensive Response” (or PD-CORE) is a composite score of three established Parkinson’s clinical clinical measures. Combined this composite may provide a more sensitive method of assessment for Parkinson’s clinical trials. # # # |

Interesting. How does this “composite” approach differ from previous attempts to introduce novel assessment systems?

When proposing a new assessment score, the typical practise has been to test it on participants in large natural history cohorts that track individuals with a condition over time. This allows for long term follow ups and evaluations.

It could be easily argued though that such an approach represents a time consuming and costly method of generating new clinical tools.

Have composite scores been proposed before?

The idea of composite scores has been explored in Parkinson’s before. For example:

Authors: Makkos A, Kovács M, Aschermann Z, Harmat M, Janszky J, Karádi K, Kovács N.

Journal: Mov Disord. 2018 May;33(5):835-839.

PMID: 29488318

In this study, the researchers were evaluating the feasibility of combining various components of the MDS-UPDRS into composite scores. Their results were supportive of the application of various MDS-UPDRS-based composite scores.

There have also been efforts to generate composite scores for other neurological conditions. A good example is ADCOMS for Alzheimer’s:

Authors: Wang J, Logovinsky V, Hendrix SB, Stanworth SH, Perdomo C, Xu L, Dhadda S, Do I, Rabe M, Luthman J, Cummings J, Satlin A. J

Journal: Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016 Sep;87(9):993-9.

PMID: 27010616 (This report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this report, the researchers found that a composite (of four Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale–cognitive subscale items, two Mini-Mental State Examination items, and all six Clinical Dementia Rating—Sum of Boxes) demonstrated improved sensitivity to clinical decline over individual scales for prodromal Alzheimer’s, Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), and in mild Alzheimer’s dementia.

They called this the Alazheimer’s Disease Composite Score (or ADCOMS), and it is now progressing through a testing/validation process being conducted by the Coalition Against Major Diseases (a component of the Critical Path Institute).

I am left wondering if – in a different life – the climber Joe Brown would have been a fan of post hoc analysis. Looking for new ideas, rather than focusing on the actual result. Trying to take as much away from the data as he could. I’m guessing he would have been.

It must be remembered, however, that post hoc analysis can only ever be used for hypothesis generating purposes. We cannot be seen to be ‘cherry picking’ the data and finding the result we want. Rather post hoc analysis allows us to generate new ideas/questions (using previous data) that need to be researched and tested.

There is certainly a desperate need for more sensititive methods of assessing Parkinson’s, especially in the context of a clinical trial evaluating a potential disease modifying therapy that might only be having a subtle effect on a specific aspect of the condition.

Some may question the approach used to develop the PDCORE composite score discussed in today’s post, but it was simply a hypothesis generating exercise – one that now needs to be tested (both by the researchers involved and independently). Employing PDCORE in future clinical trials (as an exploratory endpoint initially) could certainly speed up the validation of it. In addition, other investigators could use a similar post hoc analysis approach on their own data to assess (in effect building a version of PDCORE using data from their own trials) to see if there are any similarities across currently available clinical scores – and to take as much away from their data as possible.

Food for thought.

All of the material on this website is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

You can do whatever you like with it!

EDITOR’S NOTE: The author of this post is an employee of the Cure Parkinson’s Trust which was a supporter of the Bristol GDNF trial (along with Parkinson’s UK). The Cure Parkinson’s Trust is also a supporter of the PDCORE report that was discussed in today’s post. The Trust has not asked for this post to be written. This post has been written by the author solely for the purpose of sharing what the author considers interesting information.

The banner for today’s post was sourced from physicsworld.